By Eryk Michael Smith / Staff

Photos other than specified are via the Pingtung County Government.

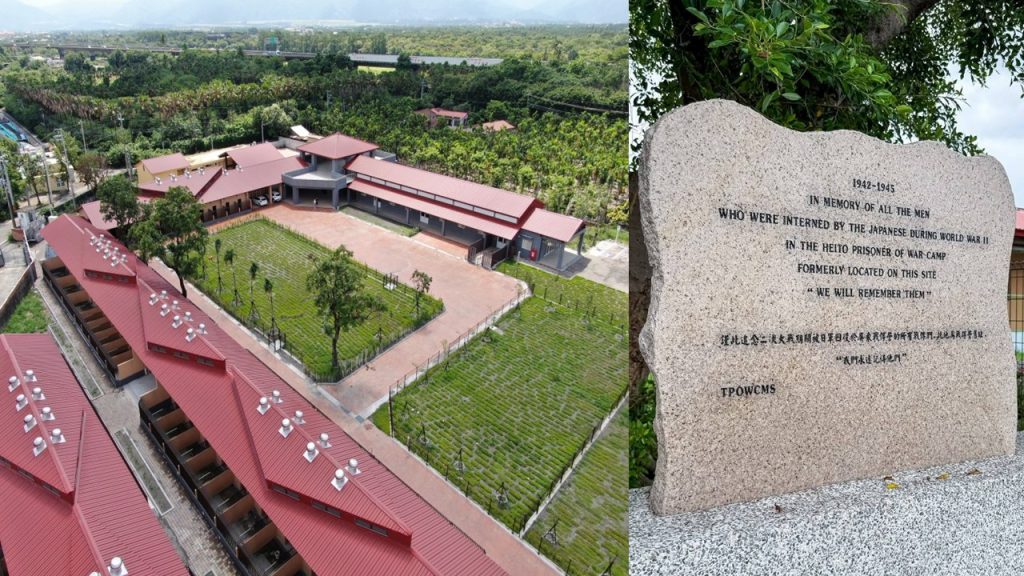

PINGTUNG — A quiet spot near Xintian Village (新田村) is now occupied by the Pingtung County Animal Shelter (屏東縣動物之家). The site, however, has undergone several transformations. It began as the Heito POW Camp under Japanese rule, later became an ROC army base, and went on to serve as emergency housing for Indigenous villagers displaced by typhoons.

The Pingtung County Government explains that the story starts in 1942, when the Japanese military converted a workers’ barracks at a gravel quarry along the Ailiao River (隘寮溪) into a POW site officially listed as the third branch camp of the Taiwan system. Spread across just under four hectares, the compound was basic: thatched roofs, bamboo fencing, wooden boards for beds. About thirty Formosan guards drafted from the colonial police watched over five to six hundred Allied prisoners, most of them British soldiers captured at the fall of Singapore, along with Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, Americans, and two Chinese POWs.

Former guard Lin Chuan-hsin (林全信) later described the camp as harsh but not as deadly as Kinkaseki in northern Taiwan. For the POWs, “less harsh” still meant exhausting labor hauling gravel from the riverbed, loading it onto rail carts bound for Kaohsiung’s Zuoying naval facilities, or carrying sugar sacks at the Pingtung Sugar Refinery. Medical care was almost nonexistent. Lin estimated that sixty to seventy prisoners died from dysentery or other illnesses, with several more killed during American air raids. Coffins ran out toward the end of the war, so bodies were wrapped in blankets and buried at the Linluo cemetery.

Yet the camp also produced moments of humanity. Prisoners were allowed to elect clergy and hold Christian services in a makeshift chapel. Lin, himself a Christian, secretly gave a Canadian POW a Bible. The man later donated it to the chapel. Some believe this small gesture helped reduce suicides and escape attempts. Decades later, the families of former POWs would travel from Britain, Canada, and elsewhere to stand at the site and read poems for fathers who never returned.

The camp closed in March 1945. After the war, Taiwanese guards helped mark the graves before the remains were sent to Commonwealth cemeteries in Hong Kong. The site was then taken over by the ROC Army and became Ailiao Camp (隘寮營區). In the 2000s, it was repurposed to shelter villagers displaced by typhoons.

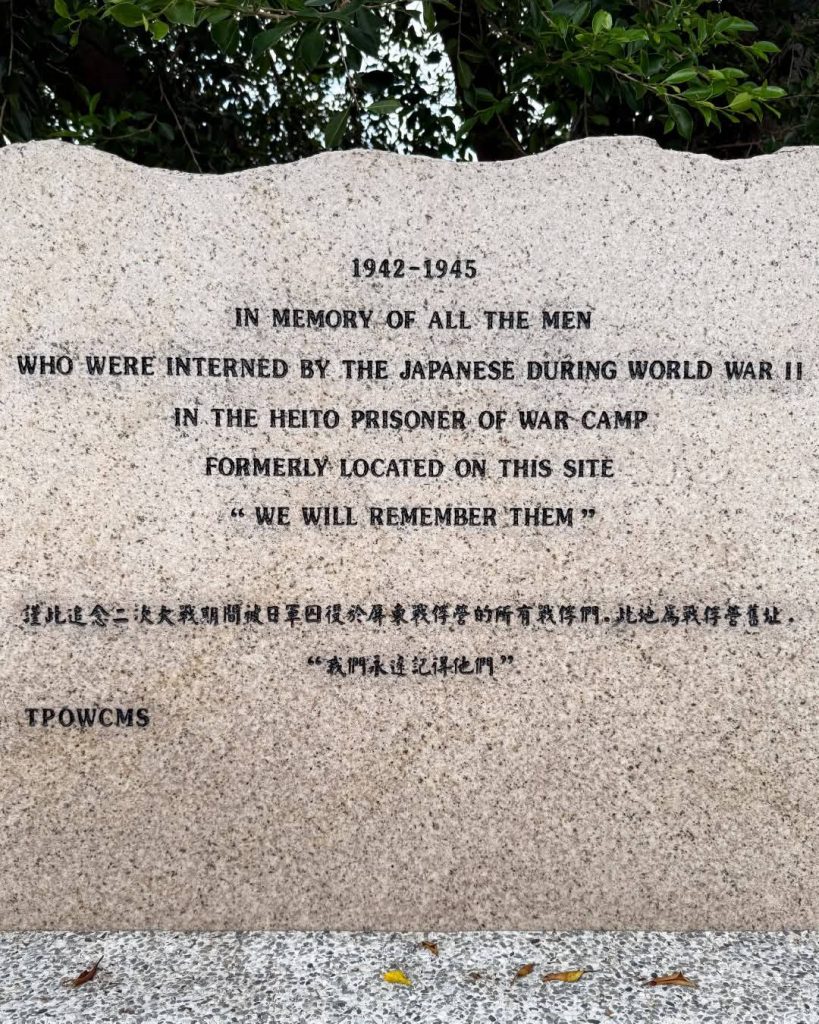

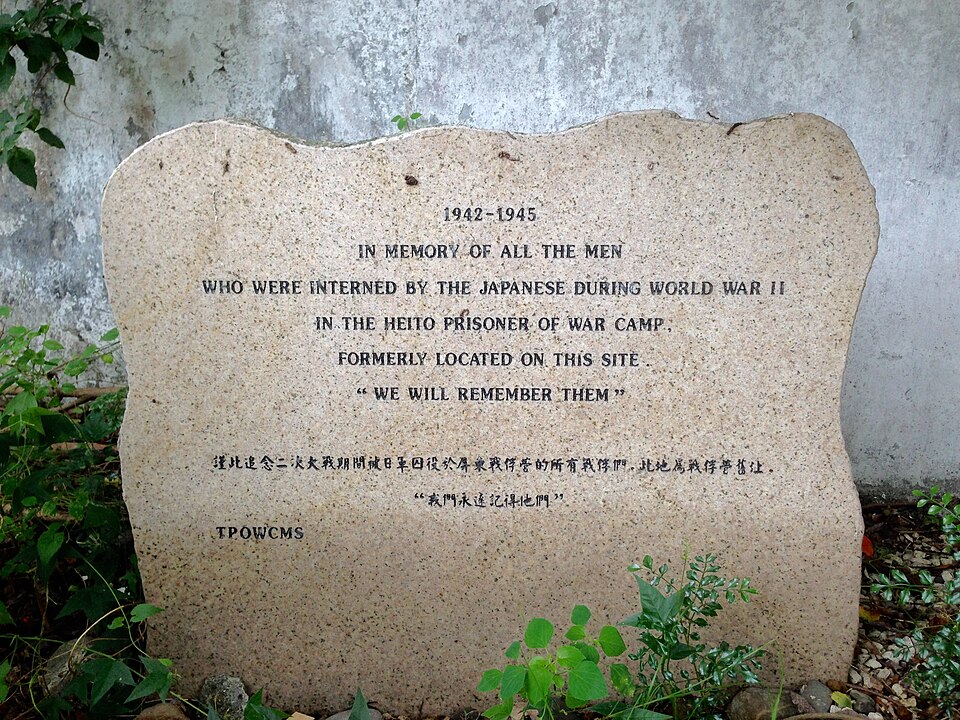

In 2004, respected researcher Michael Hurst (何麥克) of the Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society proposed installing a marble memorial outside the main gate. The monument was unveiled the same year, becoming a focal point for returning POWs and their families. Among the most widely reported visits was that of British woman Alice Myerscough, who waited more than fifty years to visit the ground where her fiancé, soldier Alan T. Bowman, died of dysentery a month after arriving at the camp. (More on that story in the translated Wiki page below.)

The site’s newest chapter began in June 2024, when President Lai Ching-te (賴清德) joined county officials to open the Pingtung County Animal Shelter. Built at a cost of NT$230 million, the 3.747-hectare complex functions as a “life-education campus,” combining animal housing with veterinary care, grooming, behavior training, and wildlife rescue.

The layout is deliberately open, with age-based housing zones, ventilation corridors, interaction areas, isolation and medical rooms, and green-energy design features. Officials say they want the shelter to be both functional and community-friendly. Some on-site staff told the media that the distant mountain lines at sunset offer scenery that might seem unexpectedly peaceful for a place with such a difficult past.

A small gallery next to the main shelter building preserves the wartime history, displaying material about the old camp and its prisoners. Critics argue that the redevelopment erased too much of the physical site. Supporters say the county struck a balance between present-day needs and acknowledgment of the past.

Either way, the land in Linluo Township (麟洛鄉) continues to evolve. What was once a place of confinement and loss now serves as a center for care and rehabilitation. Whether that combination feels like reconciliation or compromise will likely depend on who visits.

——————————————————————————————–

NOTE: We were unable to find an English Wikipedia page for the Heito POW camp, so we’ve attempted to translate the Chinese version below. We cannot vouch for its complete accuracy.

English translation of the Wikipedia article.

Linluo POW Camp

Linluo Ailiao Camp (Chinese: 麟洛隘寮營區) was a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp established by the Japanese military from 1942 to 1945 in present-day Xintian Village (新田村), Linluo Township (麟洛鄉), Pingtung County (屏東縣), Taiwan. After the war, the site became the Linluo Ailiao Army Camp and is now the location of the Pingtung County Animal Shelter.

Location: No. 101, Xinyi Road, Xintian Village, Linluo Township, Pingtung County, Taiwan

Coordinates: 22.656742°N, 120.548967°E

Type: Army base (postwar)

Controlling authority (postwar): Ministry of National Defense of the Republic of China

Built: 1942

POW camp period

The site was originally a workers’ barracks for a gravel quarry on the Ailiao River (隘寮溪). In 1942, the Japanese military converted it into a POW camp, designated as the third branch camp of the Japanese POW camp system in Taiwan. It officially opened on 17 July 1942 and covered a little over 3 hectares. The camp stood in a remote, desolate area on a gravelly riverbed. Facilities were simple: thatched roofs, with only the toilets and bed boards made of wood, and the compound encircled by bamboo fencing.

Thirty Taiwanese guards from the main island of Taiwan were seconded by the Governor-General’s Police to serve as squad leaders and sergeants. They themselves were strictly controlled by more senior colleagues; if they moved too slowly, they would be slapped or beaten, and were sometimes ordered to slap each other.

Lin Chuan-hsin (林全信) and the other 29 Taiwanese guards watched over some 500–600 POWs captured in the Pacific War, including British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealander, and American prisoners. Most were British troops transferred from the Battle of Singapore. In addition to white Europeans, there were also Black prisoners and two Chinese prisoners.

At first, the rations at the camp were relatively good. Fresh vegetables were brought in daily by truck from Pingtung City, and raising pigs, chickens, and ducks was allowed. POWs who were ill and unable to perform hard labor were transferred to the Baihe Branch Camp (白河四分所). Compared with other camps in Taiwan, such as the Kinkaseki (金瓜石) POW camp, conditions here were considered somewhat less severe. The camp had a chapel where POWs could hold worship services, and they elected their own clergy. When International Committee of the Red Cross representatives came twice a year to inspect, they brought beef jerky, milk powder, coffee, chocolate, and other goods. The Japanese would deliberately display large amounts of fruit, follow closely behind the inspectors, and the POWs would speak in unison, saying that they were well fed and had not been beaten or humiliated. In reality, the Japanese guards beat POWs in secret. On one occasion, several bags of fine sugar went missing in the camp; when it was discovered that POWs had stolen and hidden them in pillowcases, they were severely beaten.

When POWs fell ill, they received virtually no medical treatment. They were forced to work like slaves, digging gravel out of the riverbed, loading it onto small rail cars, and transporting it to Kaohsiung Harbor for the construction of Zuoying Naval Port. At other times, they were sent to the Pingtung Sugar Refinery to handle heavy sacks of sugar. Cases of mental breakdown were common, and some POWs committed suicide.

Lin Chuan-hsin estimated that around 60 to 70 British, American, and Canadian POWs died in the camp from dysentery and illnesses due to the climate and environment. Some POWs were also killed in American air raids. Toward the end of the war, there was a severe shortage of coffins; corpses were wrapped in blankets and placed in a coffin, transported by light railway cart to the Linluo cemetery (now the parking area for garbage trucks in Linluo), where fellow POWs held a simple Christian burial service. After the body was placed in the grave, the empty coffin would be taken back and reused.

Although guards were strictly forbidden to converse or socialize with POWs, Christian guard Lin Chuan-hsin befriended a Canadian soldier and gave him a copy of the Bible. The Canadian then donated the Bible to the camp chapel. Gradually, the number of suicides declined, and escape attempts ceased. Lin speculated that this may have been the main reason the Japanese allowed the chapel to remain and did not pursue punishment against him for giving away the Bible.

According to Yoshiaki Chayano’s book Dai Tōa Sensōka Gaichi Furyo Shūyōjo (茶園義男《大東亜戦下外地俘虜収容所》) and records from POW information agencies, the camp was officially closed on 15 March 1945. As the war situation eased somewhat, island-based guards adopted more lenient, “soft” methods of control toward POWs. Except for the camp commandant Tamaki (玉木) and two others who were sentenced to fifteen years, few were imprisoned after the war.

After the camp closed

After the war, former guards including Yang Teng-ch’ing (楊登清), Hung Wan-feng (洪萬鳳), and Chiu Ch’uan-tsai (邱全財) re-marked the POW graves with name plaques, and the remains were sent to foreign military cemeteries in Hong Kong. The site later became the Ailiao Army Camp of the Republic of China Army; today, it is home to the Pingtung County Animal Shelter (“Maoxiaohai Paradise,” 毛小孩樂園).

Former guards once invited their Japanese ex-superiors for a reunion. At one such meeting, when Lin Cheng-hsin (林正信) offered a piece of native free-range chicken to a former superior named Katō, the man tapped Lin on the head with his chopsticks and scolded him for poor hygiene. Lin joked that he was used to being hit by this superior, just as he had been in the past.

On another occasion, Lin went to a fabric shop on Shennong Street (神農街) in Tainan and met a former colleague surnamed Kuo, who wanted to seek out another ex-guard surnamed Chuang, then living in Ch’i-shan Hsi-chou-tzu (旗山溪州仔), to take revenge for beatings in the camp. Lin persuaded him to give up the idea.

In August 1999, a Canadian in his fifties named Kent came to visit Lin Chuan-hsin, accompanied by Michael Hurst (何麥克) of the Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society. Kent said that his father had always told him, from the time he was a child, that a Taiwanese man had given him a Bible in the camp, and that their family had never forgotten this kindness.

Photos from Wiki:

The camp’s guard post.

Memorial inscription

Interior of the camp

Original narrow-gauge rail line

In November 1999, the Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society received a letter from a British woman, Alice, who was searching for the camp where her fiancé, Alan, had died. Michael Hurst and Huang Li-hsia (黃麗霞), secretary-general of the Donggang River Conservation Association (東港溪保育協會), helped arrange her trip to Taiwan, which took place in June 2002. Alice had met Alan at church youth fellowship when she was 15. Alan was later captured in Singapore and sent to this POW camp, where he died of dysentery just one month after arrival. Alice said: “If Britain and Taiwan were not separated by the sea, I would have walked here. I would have walked all the way to Taiwan, to the place where Alan is buried.”

Hurst proposed erecting a marble memorial at the site. On 20 October 2004, he visited the camp with Legislator Ts’ao Chi-hung (曹啟鴻), surviving guards Lin Chuan-hsin and Yang Teng-ch’ing, and military personnel to inspect possible locations for the monument. They decided to place it outside the main gate of the camp: a location convenient for public visits and commemorations, and practical for the camp to help watch over the monument.

On 16 November 2004, seven former British POWs and more than ten family members attended the unveiling of the POW memorial. Local representatives included Pingtung County Deputy Magistrate Ku Yuan-kuang (古源光), Linluo Township Chief Tseng Sen-ts’ai (曾森財), former guards Lin Chuan-hsin and Yang Teng-ch’ing, as well as military officers.

At the ceremony, Alice softly recited:

“A band of boys marched forward in glory;

they bowed their heads, closed their eyes, and wept quietly,

their young journeys ending here.

A band of men marked by the years

gave everything they had,

fighting for their country and for freedom,

speaking softly of the blanks in their lives.

These people, who bear such deep suffering,

traded their blood, their tears, and their sorrow

for our tomorrow…

yet the price of peace has been so terribly high.”

Later, the military camp was decommissioned. The site was used in 2007 to house Rukai (魯凱族) villagers from Wutai Township (霧台鄉) displaced by Typhoon Sepat (聖帕颱風), and also served as a venue for cultural activities.

In 2010, two elderly sisters from London, Bessie and Carol, aged 73 and 68, visited the memorial, leaning on walking frames as they tearfully recited a poem. Bessie’s father, Henry Emmanuel Lee, had been captured at age 23 and held as a POW in the camp for three years under the number 4620631. He died in an air raid shortly before the end of the war and was later buried in Hong Kong. Bessie had travelled to Hong Kong at age 70 to pay her respects, and this was her first trip to Taiwan; she composed a poem for her father at the memorial.

On 14 November 2017, British visitor Louis Follon and his son came to the site to pay their respects, accompanied by US-born pastor Morris Su (蘇慕理), who resides in Taiwan. Yang Teng-ch’ing, then 96 years old and a former Taiwanese guard at the camp, attended the event in a wheelchair. Louis’s father, Alfred J. Follon, had been captured in 1942 and transported from Southeast Asia to this camp, where he was held for about three years before returning to Britain at age 21. He died in 2007 at the age of 84. Because the camp had a small river and a railway bridge, the scenery resembled Myanmar, and Alfred always thought he had been imprisoned somewhere in Southeast Asia. Louis said that only this year, through the Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society, did he discover that his father had actually been held at the Ailiao Camp in Linluo. He therefore decided to visit, marking his first trip to Taiwan.

References

Li Hui-t’ang. “Sun Moon Culture Publishing Donates Books: Spreading the Love of Reading in Pingtung” (日月文化出版社捐書 書香傳愛屏東). The Epoch Times (大紀元時報). 20 October 2015.

Li Chan-ping. “Unforgettable Prison in My Heart – Pingtung Linluo Third Branch Camp” (〈難忘心中監獄——屏東麟洛第三分所〉), in Advancing into Borneo – Taiwanese POW Guards (《前進婆羅洲-台籍戰俘監視員》). Academia Historica, Taiwan Branch of the National Archives (國史館台灣文獻館). 1 August 2005. ISBN 9860016550.

“POW Camps Outside Japan” (日本国外の捕虜収容所). POW Research Association (POW研究会).

Lo Hsin-chen. “South: Father Imprisoned Three Years at Linluo Ailiao – British POW’s Descendants Pay Their Respects” (〈南部〉父囚麟洛隘寮3年 英戰俘後代追思). Liberty Times (自由時報). 15 November 2017.

Wei Ching-shui. “World War II Linluo POW Camp Erects Memorial” (二次大戰麟洛俘虜營立紀念碑). ETtoday News. 17 November 2004.

Hou Ch’ien-chüan. “South: Elderly British Sisters Tearfully Visit the POW Camp Where Their Father Died” (〈南部〉英國老姊妹 含淚訪父身故戰俘營). Liberty Times. 17 November 2010.

Wei Ching-shui. “Linluo WWII POW Camp to Establish Memorial” (麟洛二次世界大戰俘虜營 將設紀念碑). ETtoday News. 21 October 2004.

Lin Chuan-hsin. “Old Soldier’s Notes” (〈老兵札記〉). Keng-hsin Weekly (《耕莘週刊》), Taiwan Church Press, Presbyterian Church in Taiwan. 30 November 2003, no. 378.

Hou Ch’ien-chüan. “Old Soldiers Never Die – POW Camp Memorial Unveiled” (老兵不死 戰俘營紀念碑成立). Liberty Times. 17 November 2004.

“The Clouded Leopard Descendant Who Came to Treasure Tribal Culture Through Disaster – The Life Story of Rukai Tribal Member Lee Chin-lung” (因災變而更珍惜部落文化的雲豹傳人-魯凱族李金龍的生命故事). China Times (中國時報). 8 October 2015.