KHT Staff On-Site Report

For many long-term foreign residents in Taiwan, one of the enduring pleasures of life on the island is the sense that discovery never quite ends. Despite Taiwan’s compact size, its layered history, regional diversity, and mix of cultural influences mean there is always something new to notice, even in places passed daily without a second thought.

Taoist temples are a case in point.

While Buddhist and Confucian temples tend toward restrained symmetry and more subdued ornamentation, Taoist temples are visually exuberant. Many are dedicated to Mazu (媽祖), Taiwan’s most widely venerated sea goddess. Their rooftops are often crowned with phoenixes, dragons, and other auspicious creatures. Inside the temple are often figurines of immortals and historical figures arranged in elaborate ceramic scenes.

The craftsmanship of temple rooftops often remains invisible, as it’s quite literally placed high above eye level. Those interested in seeing it up close are advised to visit a workshop in Chiayi County’s Xingang Township, where one village has played an outsized role in sustaining Taiwan’s temple ceramics tradition.

Bantou Village is home to the Bantao Kiln Craft Park (板陶窯交趾剪黏工藝園區), a working studio and exhibition space dedicated to two traditional temple crafts: koji pottery and jiannian, or cut-and-paste mosaic. Both techniques are widely used in the sculptural roof figures and reliefs that define Taiwanese Taoist temple architecture.

Koji pottery is a low-fired ceramic tradition known for its sculptural flexibility and muted but durable glazes. Jiannian, by contrast, is a labor-intensive mosaic technique in which porcelain is cut into small fragments and embedded into stucco frameworks, producing vivid, light-catching surfaces. The two crafts are often combined on temple roofs, where individual figures are assembled into complex narrative scenes.

The “scales” that make up a decorative dragon, for example, are made by breaking ceramic bowls. A tool helps mark the break line, and then it’s turned into a scale-like piece that’s cemented onto a frame. The technique uses steel wire as “bones” and plaster as “flesh.” Artisans then use pincers to clip bits of colored ceramics. Embedded in the plaster, these clips become the skin.

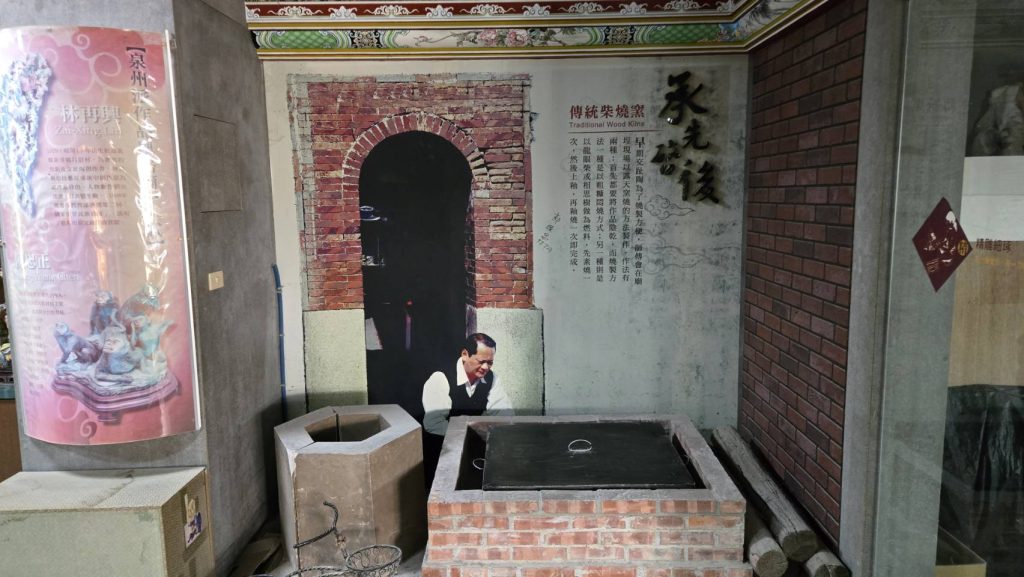

Xingang Township became a center for these crafts in the early 20th century following major earthquakes in 1904 and 1906 that damaged Fengtian Temple (奉天宮), first built in 1811. Master craftsman Hong Kun-fu (洪坤福, 1865–unknown) was invited from southern Fujian to assist with reconstruction and train local apprentices, laying the foundation for the region’s temple ceramics industry.

As demand for handmade temple work declined and cheaper factory-made imports entered the market, Banto Kiln sought new ways to sustain the craft. With government support, the workshop was transformed into a cultural tourism site in 2005, combining active production, exhibitions, educational programs, and public art installations. The shift not only stabilized the business but also helped anchor broader community revitalization efforts in Bantou Village.

Today, Bantao Kiln offers rare access to a craft tradition most people encounter only in finished form.

During a recent international media tour organized by the Chiayi County Culture and Tourism Bureau, journalists were taken to the workshop — which seems to have several names, including the Bantao Kiln Koji Pottery & Jiannian Crafts Cultural Base (板陶窯交趾剪黏工藝園區). Tour guides explained that while new temples might get their dragon or phoenix from a 3D printer, any temple with a history will seek replacements from this site in Chiayi that’s central to Taiwan’s temple ceramics tradition. The workshops there have supplied roof sculptures, relief panels, and decorative elements for some 70% of temples across the island, reports say, playing a major role in sustaining the visual language of Taiwanese Taoist architecture.

By opening these workshops to visitors, Chiayi offers rare access to a craft tradition that most people encounter only after it has been mounted high above eye level. It is a reminder that Taiwan’s temples are not static monuments, but evolving cultural expressions shaped by skilled hands, inherited knowledge, and continuing belief.