By KHT Staff

Some readers may already be familiar with the Liudui Hakka, a self-organized militia that emerged as a significant force in southern Taiwan during the Qing period. Their reputation was forged in 1721, after a major uprising led by Zhu Yi-gui (朱一貴)—often remembered locally as a Kaohsiung duck farmer turned rebel. The Hakka initially allied with Zhu, but later broke with him and sided with the Qing court. Their loyalty came late, but it was not forgotten: the emperor rewarded the Liudui militia with an imperial plaque honoring their service.

From the Qing era onward, Hakka communities appear repeatedly in Taiwan’s turbulent historical record, often at moments when the island was contested, invaded, or reorganized by outside powers. That legacy has resurfaced in recent months with the discovery of a previously lost mass grave in Changzhi Township (長治鄉), Pingtung County—a find that has reopened a painful chapter from 1895, the year Taiwan was transferred to Japanese rule.

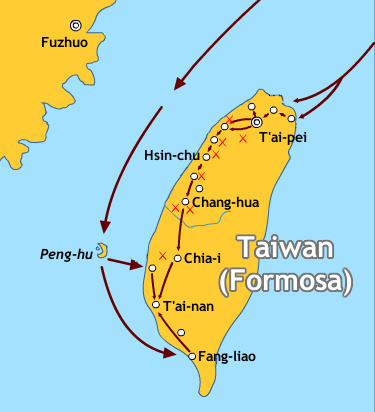

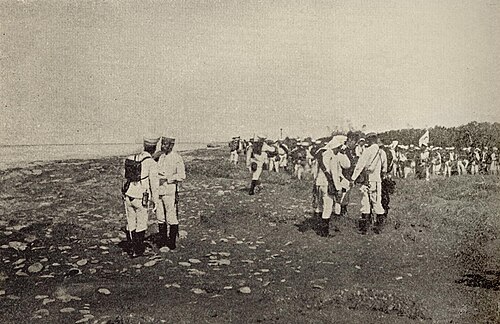

A Taipei Times article notes that according to township officials and local historians, the grave is believed to contain the remains of more than 200 Hakka volunteer fighters, many of whom were killed while resisting Japanese forces under the leadership of Chiu Feng-yang (邱鳳揚), a prominent Liudui Hakka leader and supporter of the short-lived Republic of Formosa. Their deaths came during the violent final months of armed resistance, as Japanese troops moved south to consolidate control of the island following the Treaty of Shimonoseki.

Stubbornness, resolve, sacrifice

In a 2017 exhibition, the Taiwan Hakka Museum reflected on a quality often attributed to Hakka communities: stubbornness. The museum suggested that the term is neither purely positive nor negative, but instead reflects endurance, independence, and a willingness to persist under pressure. From frontier settlements to industrial marginalization, Hakka society, the exhibit argued, has tended to advance “step by step,” quietly but firmly, building what it sees as morally defensible communities.

Whether labeled stubbornness or resolve, that quality was tested severely in 1895. By then, few in Taiwan could have been unaware of the military power of newly industrialized Japan, which had defeated the Qing Empire in a matter of months. Estimates commonly cited in historical records suggest tens of thousands of Qing troops were killed or wounded, while Japanese losses—many from disease—were far lower.

Against those odds, Hakka volunteers still mobilized, many almost certainly understanding that resistance was unlikely to succeed.

A grave lost and found

The Battle of Huoshaozhuang (火燒庄戰役) took place in 1895. After the fighting ended, the bodies of fallen volunteers were reportedly transported by ox cart and buried together at what later became Changzhi Township’s Second Public Cemetery. Over time, the precise location of the burial faded from public memory, even as descendants continued annual memorial rites at Dawupu Zhongyong Gong (大武埔忠勇公).

A tombstone inscribed “Changxing Dawupu Joint Tomb” (長興大武埔合祀靈墓) was erected, but the grave itself remained elusive until it was uncovered earlier this year during a cemetery relocation project.

Changzhi Township Mayor Wu Liang-ching (吳亮慶) said the discovery has renewed local attention to the site’s importance, calling it a rare physical reminder of armed civilian resistance during one of the most consequential transitions in Taiwan’s modern history.