By John Ross

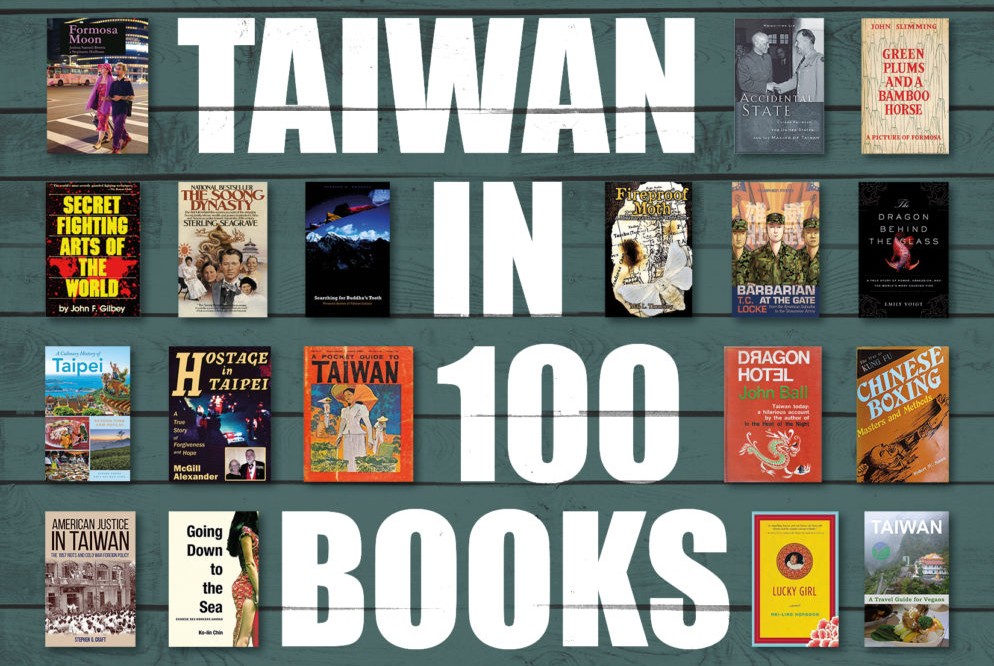

The Kaohsiung Times continues its serialization of John Ross’s Taiwan in 100 Books with the second half of Chapter Two, which examines the end of Dutch rule on Formosa.

* * *

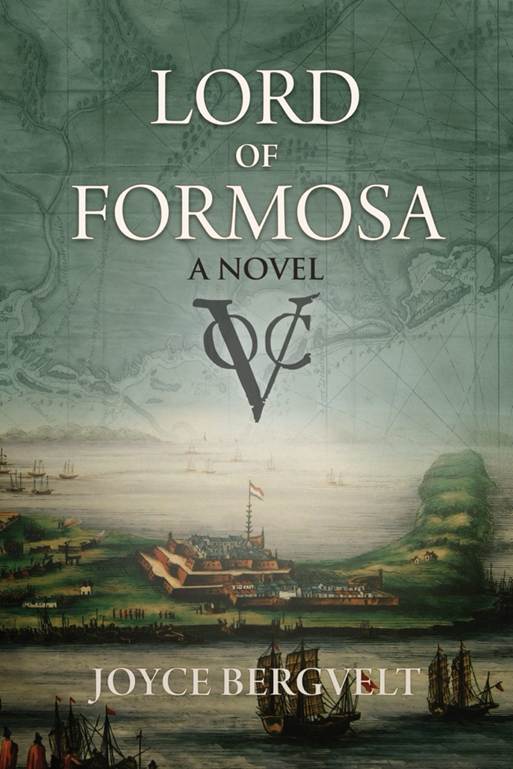

At times Lost Colony reads like a novel, which raises the mystery over the long absence of fictional works about Koxinga and his fight with the Dutch. That it was only in 2018 with Joyce Bergvelt’s Lord of Formosa that we saw a novelized examination of the conflict is a reminder that there are still big stories out there awaiting a willing writer. Dutch-born Bergvelt gives us a complete story of Koxinga from his birth in Japan in 1624 – conveniently the very same year the Dutch founded their settlement in Taiwan – to his battle of wills with Governor Coyet. She also cleverly gives the VOC interpreter He Ting-bin an important role in the novel. Not only does He Ting-bin provide the spice of treachery and intrigue, but as a character moving between the worlds of the Dutch and the Chinese, he helps weave the two streams of the novel together. And he truly was one of the most important figures in the real historical drama.

He Ting-bin was a middle-man playing both sides, telling both Koxinga and the Dutch what they wanted to hear, and whatever would work best for his own private squeezes. When his Dutch employers discovered that he had been secretly extracting heavy tolls from Chinese merchants, he was arrested, tried, and found guilty. He was fired and fined. We next find him in Xiamen with a map and a dishonest sales pitch for Koxinga: that Taiwan was an Eden of vast fertile fields and enormous potential – perfect as a new base. Weakly guarded by the Dutch, it could be taken “without lifting a finger.” Without He Ting-bin’s assurances of riches and easy victory, Koxinga may well never have sought to oust the Dutch.

Of all the Taiwan novels I’ve read, Lord of Formosa stands out for its great cinematic potential. As yet, no English-language work set in Taiwan has made it to the big screen, though several big-budget American film adaptations of novels set elsewhere have been shot on the island; inSand Pebbles (1966), from the 1962 novel by Richard McKenna, locations near Keelung stood in for the Yangtze River in the 1920s. And in Martin Scorsese’s Silence (2017), based on Shusaku Endo’s 1966 novel of the same name, Taiwan was transformed into seventeenth-century Kyushu. Taiwanese director Ang Lee won the Academy Award for Best Director for his 2012 film adaptation of Yann Martel’s Life of Pi. Much of the film was shot in Taiwan, though this was largely done in a specially built giant wave tank.

* * *

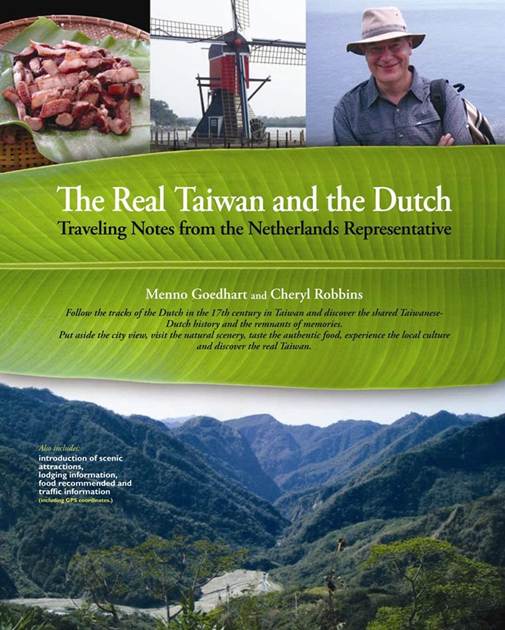

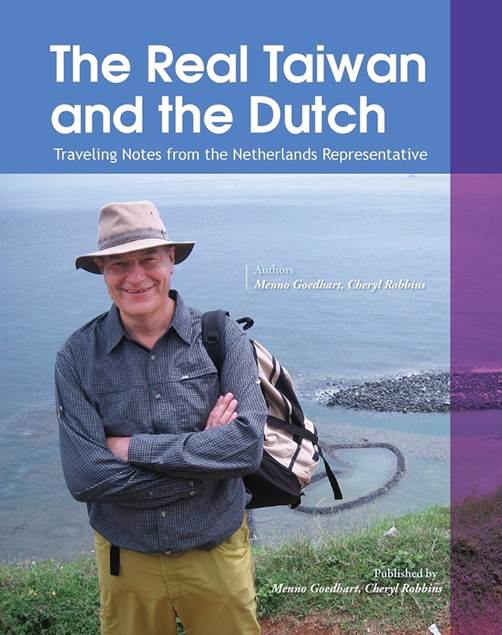

For history buffs looking to track down the vestiges of the Dutch period, there’s a guidebook dedicated to the task: The Real Taiwan and the Dutch: Traveling Notes from the Netherlands Representative (2010), by Menno Goedhart and Cheryl Robbins.

My first impressions of this Dutch-flavored guidebook were decidedly mixed. Beautifully printed and lavishly illustrated, it looked, however, with its multitude of pictures of the author and local food specialties, like a cross between a Tourism Bureau publication and a typical Taiwanese Facebook feed.

I admit I’ve always had a curmudgeonly attitude toward Taiwanese food-tourism culture and especially its elevated reverence for traditional local dishes. In our hyper-interconnected world there’s a reason a food is only a local specialty: it’s probably not good enough to spread beyond that particular place. If a dish is sufficiently tasty (beef noodles, for example) or even middling (the likes of Chiayi turkey rice), then it will spread. As a result of this natural sorting, the “famous” local specialties you encounter are usually worse than normal, everyday fare. Although the nondescript cookies, noodles, sticky rice balls, and other offerings provide nostalgia value for Taiwanese customers, for Johnnie foreigner they are consistently underwhelming. And it’s not because the modern versions are inferior to the originals. Let’s face it: most of these dishes were never that great; what constituted a treat for an impoverished peasant in the 1950s and before – when even white rice was something of a luxury – is going to struggle to impress in our current age of 24/7, all-you-can-eat overabundance.

Happily, The Real Taiwan and the Dutch proved more substantial than I thought it would be. It’s a delightful resource for travelers, residents, and history enthusiasts, a 270-page guide focused on getting off the beaten path to explore Taiwan’s contemporary aboriginal cultures and the old Dutch heritage. The book contains hundreds of photographs, some maps, lots of practical travel information (complete with addresses, phone numbers, accommodation recommendations), and, as I mentioned earlier, a Taiwanese-level dedication to eating; restaurants and signature regional dishes are given a lot of space.

The book’s main author, Menno Goedhart, was, from 2002 until his retirement in 2010, the Netherlands’ representative at their Trade and Investment Office (i.e., the de facto embassy) in Taipei. Goedhart stayed on after his retirement, settling in Xinhua, Tainan, to further his investigations into Taiwan’s Dutch heritage and continue his work promoting Dutch–Taiwan cultural ties.

The Real Taiwan and the Dutch covers the core Dutch area of Tainan, the Penghu Islands (strategically located midway between China and Taiwan, the Dutch had settled there briefly), the East Coast, Chiayi, and Pingtung, as well as a chapter on “Other Places” (including Danshui and Keelung, northern outposts where the Dutch built forts). Of Danshui’s old fort, Goedhart says the name often used, Fort San Domingo, is wrong. This earlier Spanish fort was destroyed and the current building completely Dutch, so it should be called Fort Antonio after Governor General Antonio van Diemen. Sounds reasonable to me, though I’m of course partial to Antonio van Diemen; it was his drive to explore the Pacific that led to Abel Tasman discovering New Zealand in 1642. Note how Fort Zeelandia in Tainan and New Zealand share a common etymological origin, being named after Zeeland (“Sea Land”), the westernmost province of the Netherlands.

Co-author Cheryl Robbins is a Taiwan-based writer and translator. While working as a reporter for the English-language Taiwan News, she interviewed Goedhart several times and discovered a mutual interest in the country’s aboriginal cultures. Robbins and Goedhart started doing research trips and writing the book before finding a publisher. Coverage in Chinese-language newspapers on Goedhart’s project led Taiwan Interminds Publishing to approach Goedhart. They published a Chinese-language version of the book at the same time as the English version. (Yes, now all the restaurant coverage and food photos make sense!) No Dutch-language edition was produced, or needed; the English version was sold in the Netherlands, a credit to the exceptional English-language ability of the Dutch.

Robbins followed up this project with a trilogy of bilingual guidebooks for tourists looking to visit Taiwan’s aboriginal areas: A Foreigner’s Travel Guide to Taiwan’s Indigenous Areas. The three volumes are: Northern Taiwan, Central and Southern Taiwan, and Hualien and Taitung.

(Above left: paperback cover, 2010; above right, cover for ebook, 2020)

Although casual in style, the historical information in The Real Taiwan and the Dutch is top-notch. I was amazed (and slightly embarrassed) to learn about an important Dutch site just a 25-minute drive from where I live. Goedhart tells the forgotten story of Fort Vlissingen, in the village of Haomeili in Budai Township, Chiayi County. Built in 1636, on a sandbar in the estuary of the Bazhang River, it was destroyed in severe flooding in 1644. A replacement fort was built on the opposite bank upon safer ground. Nothing remains of Fort Vlissingen, though Goedhart was able, with the help of an enthusiastic local researcher, to discover the likely site, now marked by a stand of old banyan trees. Goedhart also relates a story he heard from the Haomeili locals about how a Mazu statue (perhaps dating to the 1580s and among the oldest in Taiwan) was brought inside the fort for protection during a flood and thus saved, then given the moniker “Governmental Mazu.”

As with Fort Vlissingen, going on the trail of Dutch-era ruins requires a certain talent for DIY augmented reality. Outside of the forts in Tainan and Danshui, there are few physical historical remains to see, so you have to superimpose the ghosts of yesteryear onto the often uninspiring modern landscapes and cityscapes.

During Goedhart’s travels, he was surprised by how widely the Dutch had explored and settled and by how many people claimed to have Dutch ancestors, something of which they were proud. He was welcomed on his explorations with great warmth, being adopted as a member of the Tsou tribe in Chiayi, made a chieftain of the Rukai, and an honorary citizen of Tainan.

A black-hearted cynic that I am, I take the rose-tinted Dutch connections with a healthy dose of salt. The Dutch were more ruthless tax collector than benevolent older brother. When Koxinga and his troops landed, the aborigines in the area – the VOC’s first native allies – immediately went over to the new arrivals. As Andrade writes in Lost Colony: “It was astonishing how fast they switched sides.”

Thirty-eight years of VOC rule, more than a generation of missionary work, and how little it counted when it really mattered; there were no loyal legions of natives rising up to help their Christian brothers and preserve the blessings of Pax Hollandia. The tribesmen were instead collecting Dutch heads in exchange for reward money.

Chiu Hsin-hui, an assistant professor of history at National Tsing Hua University, writes in her superb but expensive (US$125 for the e-book, anyone?) The Colonial “Civilizing Process” in Dutch Formosa, 1624–1662: “Being freed of the obligation to attend school, the Southern Plains Formosans were jubilant as they destroyed their textbooks replete with Christian edification and went out headhunting Dutch residents.” The romanized script of the Siraya language used in these books would eventually become a sacred memory but was obviously not so treasured at the time.

* * *

Thanks for reading. In our next installment, we’ll look at the wild days of Qing rule in Taiwan.