Last week, we kicked off our serialization of John Ross’ Taiwan in 100 Books with the martial arts hoax, Secret Fighting Arts of the World. As audacious and successful as that fraud was, it pales in comparison to a 1704 work on Taiwan called An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa, an Island Subject to the Emperor of Japan.

* * *

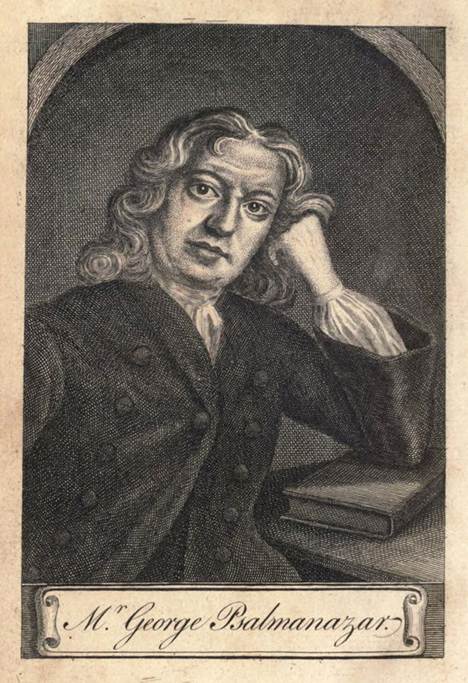

An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa, one of the most outrageous literary hoaxes ever perpetrated, was authored by a young Frenchman calling himself George Psalmanazar. He claimed to be a native of Formosa who had been abducted by Jesuits and carried off to France. Despite being threatened with the tortures of the Inquisition, he had bravely refused to become a Roman Catholic, instead finding the true faith of Protestantism.

(Images: the portrait on the left is from his memoir; all other images from his “Description of Formosa,” courtesy of the Public Domain Image Archive.)

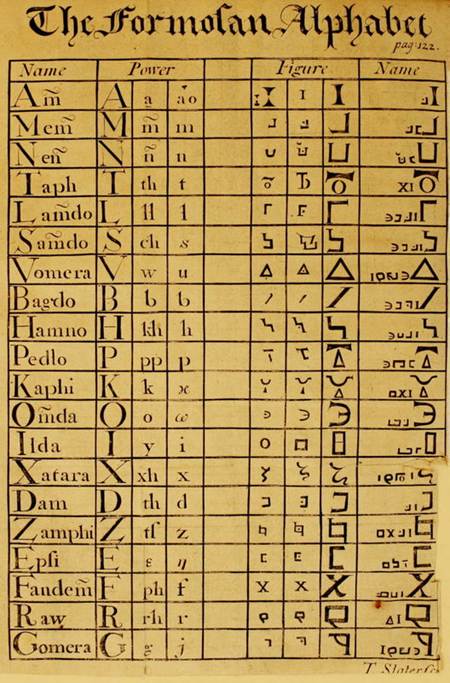

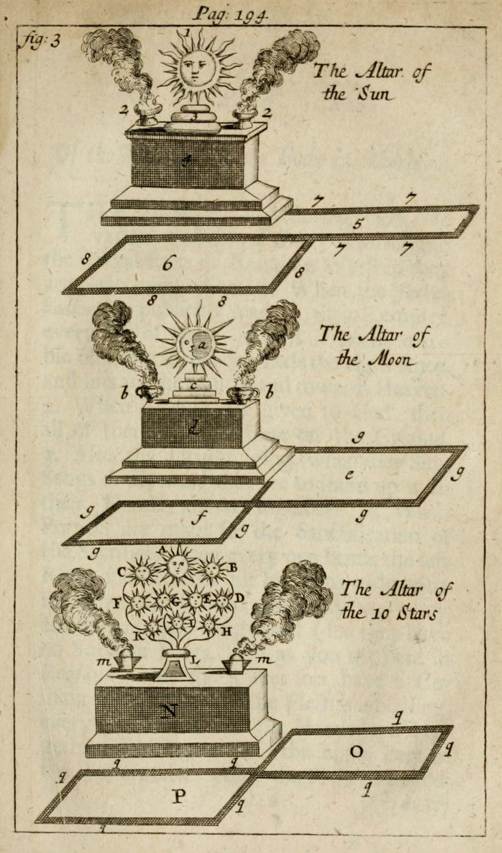

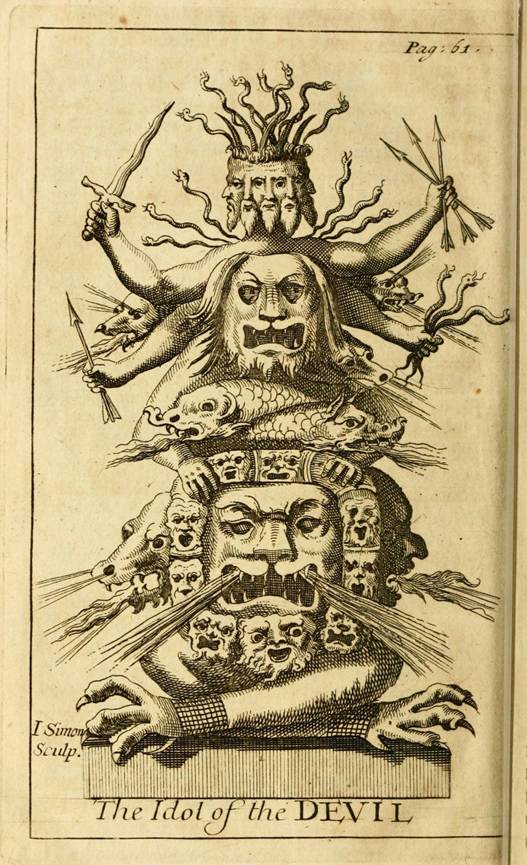

Although Psalmanazar wrote Memoirs of ****: Commonly Known as George Psalmanazar: A Reputed Native of Formosa (1764), a confessional memoir published a year after his death at the age of about eighty-four, he was a close-mouthed man, and many of the details of his life remain a mystery. We do not know his real name (his fake one, Psalmanazar, was inspired by an Assyrian king “Shalmaneser” in the Bible). Psalmanazar was born about 1679 and is believed to have come from southern France. According to his memoir, he attended a Jesuit school, but finding theology too dull, dropped out; a little later, he took to the road in the guise of a pilgrim, first as an Irishman and then as a Japanese converted to Christianity. Discovering that soliciting alms was easier the more exotic his disguise, he decided to pass himself off as a Japanese heathen. He made a little “bible” filled with figures of the sun, moon, and stars, and verses in a language of his own invention that he would chant to the rising and setting sun.

In 1702 Psalmanazar’s deceit was uncovered by Alexander Innes, an Anglican chaplain stationed with a Scottish regiment then in Holland. Innes had asked Psalmanazar to write a passage in Japanese, and then, pretending to have lost the piece, had him rewrite it. The two samples were different and Psalmanazar confessed. Innes, a greedy opportunist, thought to take advantage of Psalmanazar’s talents and invited him to England, though instead of a fake Japanese identity, the imposter was now to be a native of the even more obscure Formosa.

Psalmanazar was warmly received in England and soon became a minor celebrity. People were, however, surprised by his appearance, in particular by his fair complexion. This, he explained was because Formosans went to such great lengths to avoid the sun, living underground in the summer and in the shade of thickly wooded gardens and groves at other times.

Not only was Psalmanazar fair-skinned, but he had blond, shoulder-length hair and the facial features of a quintessential northern European. He tried to compensate by putting on a good show, which he seems to have enjoyed doing. As well as his existing habit of chanting gibberish to the skies in prayer, he came up with the ruse of eating raw meat. In his memoir, Psalmanazar writes:

“I fell upon one of the most whimsical expedients that could come into a crazed brain, viz. that of living upon raw flesh, roots and herbs; and it is surprising how soon I habituated myself to this new, and, till now, strange food, without receiving the least prejudice in my health; but I was blessed with a good constitution, and I took care to use a good deal of pepper, and other spices, for a concocter, whilst my vanity, and the people’s surprize at my diet, served me for a relishing sauce.”

Two months after arriving in London, Psalmanazar was persuaded to translate some religious texts into the supposed Formosan language. These translations were so well received that Innes prompted him to write a complete history of Formosa. And so Psalmanazar went to work, creating an untidy mix of Oriental exoticism, fevered imagination, and religious philosophy. In his memoirs he says it was written in great haste: “the booksellers were so earnest for my dispatching it out of hand, whilst the town was hot in expectation of it.”

Psalmanazar wrote the draft in Latin; this was immediately translated into English, perhaps by Innes. But just two months before it was ready to hit the printing press, every writer’s pre-publication nightmare was realized. Another account on Formosa appeared in the bookshops, and from someone who had actually been there. The book was the second edition of A Collection of Voyages and Travels (1704), edited by brothers Awnsham and John Churchill, which included A Short Account of the Island of Formosa in the Indies by Reverend Georgius Candidius, translated from the original Dutch.

Candidius, the first Dutch missionary on Formosa, had arrived there in 1627 at the age of thirty and spent the better part of a decade on the island. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) had, in 1624, established a colony in southwest Taiwan in what is now the city of Tainan, built two forts, developed agriculture and trade, and tried to convert the local aborigines to Christianity. It was a profitable colony for the Dutch. Trade consisted of exports of venison, sugar, and rattan to China, and sugar and deerskins (around fifty thousand a year) to Japan. Porcelain was shipped from China through Taiwan on to Europe.

A Short Account of the Island of Formosa describes the life and customs of the Siraya lowland aborigines. Headhunters and heathens they might have been, but Candidius considered them, all in all, “very friendly, faithful and good-natured.” They were, however, certainly a challenge for a missionary:

“drunkenness is not considered to be a sin; for they are very fond of drinking, women as well as men; looking upon drunkenness as being but harmless joviality. Nor do they regard fornication and adultery as sins, if committed in secret; for they are a very lewd and licentious people.”

And a missionary faced stiff competition in the form of the local priestesses, who presided over religious ceremonies with a considerable amount of flair. Candidius describes heavily intoxicated priestesses climbing atop a temple roof, making long orations to their gods, and beseeching them for rain: “At last they take off their garments, and appear to their gods in their nakedness.” Rain and nakedness seemed to go together.

“At certain times of the year the natives go about for three months in a state of perfect nudity. They declare that, if they did not go about without any covering whatever, their gods would not send them any rain, and consequently there would be no rice harvest.”

The strangest of the Siraya customs described by Candidius relate to marriage and mandatory abortion. He says husbands and wives lived separately until middle age, and women were not allowed to bear children till they were over thirty-five, and any pregnancies before that were terminated. The reason according to Candidius related to superstitions that a pregnant woman brought bad luck to a man when he was hunting or raiding.

You can imagine Psalmanazar staring at his desk, the Candidius account alongside his own completed manuscript, and wondering what to do. In the end, he seems to have not altered his text; but he did call out Candidius in the preface, disputing the Dutchman’s claim that Formosa had no central government. And with that, the manuscript was sent to the printer, the Black Swan – in fact, the same printer as had produced Candidius’ account. The Black Swan (formerly a pub, I assume, converted into a printer at the back and a bookshop at the front, which was a typical set-up at the time) was in Paternoster Row, a publishing street in central London near St. Paul’s Cathedral. The bookshop, along with the others on Paternoster Row, was destroyed during the Blitz in 1940. Incidentally, next door to the Black Swan was the Swan, where in 1719, Robinson Crusoe, the greatest publishing sensation of the age, was printed.

In the sequel that was released later that same year, The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, the hero of the novel briefly stops in Taiwan.

“And then we steered north, till we came to the latitude of 22 degrees 30 seconds, by which means we made the island of Formosa directly, where we came to an anchor, in order to get water and fresh provisions, which the people there, who are very courteous in their manners, supplied us with willingly, and dealt very fairly and punctually with us in all their agreements and bargains. This is what we did not find among other people, and may be owing to the remains of Christianity which was once planted here by a Dutch missionary of Protestants.”

Publication of the first edition of An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa was announced in the London Gazette of April 17–20, 1704, with the highlighted aspect being the author’s conversion from paganism. This emphasis was reflected in the book too, with the conversion story and related attacks against the Jesuits accounting for a good third of the text. In the Formosa sections, Psalmanazar described a rich land of good government, prosperous towns, and grisly customs. The inhabitants were wealthy enough to eat with utensils and dishes “made of Gold and China Earth.” The typical breakfast doesn’t sound too appetizing though:

“first they smoke a pipe of tobacco, then they drink bohea, green or sage tea; afterward they cut off the head of a viper, and suck the blood out of the body; this, in my humble opinion, is the most wholsom breakfast a man can make.”

The most shocking claim in Psalmanazar’s book was that eighteen thousand young boys were sacrificed to the gods each year; and in the second edition, published in 1705, cannibalism was added to the mix.

* * *

Next week we will continue the Psalmanazar story, covering how his Formosan claims were challenged and how he defended himself. Our French conman had some very cunning explanations to rebut his challengers, and also the confidence that came from an increasing intake of drugs.

Until then, happy reading.