CHAPTER TWO – EARLY FORMOSA: Part 1

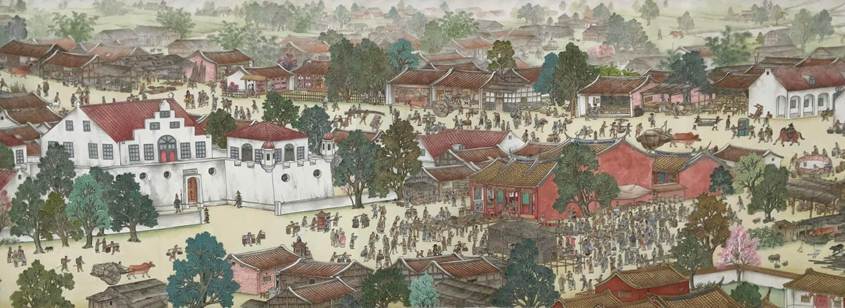

Above: A scene of what is today Tainan City, from Dr. Chen Yao-chang’s A Tale of Three Tribes in Dutch Formosa, painted by Master Shen Jian-long (沈建龍).

The Kaohsiung Times continues its serialization of John Ross’s Taiwan in 100 Books with the first half of Chapter Two, which examines the end of Dutch rule on Formosa.

* * *

But we have skipped over the story of the Dutch in Taiwan much too quickly. We should return to the early 1620s. The VOC, having failed to take Macau from the Portuguese, denied permission to establish a post on the Chinese coast, and having been told by the Ming authorities to move from the Penghu Islands to Taiwan, founded a settlement in southwestern Taiwan.

Although there were only about two thousand VOC employees – about half of whom were soldiers – the Dutch radically altered the course of the island’s history by opening it to the outside world and bringing in Chinese settlers (mostly males) to work the land. By the end of Dutch rule, between forty and fifty thousand Chinese lived in Taiwan.

Dutch rule was both harsh and exploitative, with onerous taxes on almost everything: growing rice, trading, fishing, butchering pigs, and even hunting deer. A poll tax provided the catalyst for an uprising of Chinese settlers in 1652, which was brutally suppressed. Over a period of two weeks, Dutch troops and two thousand aboriginal allies slaughtered about five thousand poorly armed peasants. These Chinese immigrants would have their chance to extract revenge a decade later.

On the morning of April 30, 1661, a massive fleet of Chinese war junks and transport ships carrying about twenty-five thousand men appeared off the coast. It was Koxinga, son of a Chinese merchant pirate and a Japanese mother, a Ming loyalist who came to Taiwan to establish a base from which to keep resisting the Manchus and their newly established Qing dynasty.

Koxinga landed his troops a little to the north of Fort Zeelandia in Anping, and was welcomed by the Chinese inhabitants as a liberator. The Dutch, trying to prevent the invaders from grabbing a strong foothold, threw a force of 240 men against an advance party of four thousand Chinese troops. The Europeans soon found they had underestimated Koxinga’s men. This time the Dutch weren’t fighting unarmed farmers. Musket fire was answered with a rain of arrows and such a ferocious attack that the Dutch fled in terror, some flinging their weapons aside in haste to escape. Only half the force made it back to the fort.

Koxinga gave the Dutch an ultimatum – leave now with all their goods or stay and perish. The situation for the Dutch was hopeless; there were only about twelve hundred men and limited ammunition. Nonetheless, they decided to stay and fight. The Chinese attacked several times but were driven back with heavy loss of life. Koxinga, deciding to give priority to housing and feeding his troops and followers, chose to lay siege to the stronghold and wait. A terrible fate befell the Dutch who were caught outside the fort. Charged with inciting the locals to revolt, the men were killed, some crucified or impaled; and the women were killed, divided among the commanders, or sold off.

The Dutch held out in Fort Zeelandia for nine months before a traitor provided valuable advice on overcoming the defenses, which, combined with new, persistent attacks, made their position untenable. The stubborn defenders, now reduced by fighting and especially disease to just four hundred, had earned the grudging respect of Koxinga, who let them surrender on generous terms: they could leave on their ships, and even take some of their cash and possessions with them. Furthermore, they were given the honor of being allowed to leave their fort marching, fully armed, bearing banners, and with drums beating.

The deadly fight for Taiwan centered on Fort Zeelandia is Taiwan’s single greatest story. Other events in Taiwan’s history are missing some narrative ingredients and a certain X factor. Take, for example, the Japanese takeover in 1895, which was the result of Peking ceding the island as war reparations for events in Manchuria and Korea; although some Taiwanese resisted the Japanese fiercely, the sporadic, drawn-out, one-sided fighting doesn’t lend itself to a gripping storyline. Likewise, the end of the Japanese colonial period was determined by events elsewhere (e.g., the dropping of the atomic bombs in 1945); and the Chinese Nationalists didn’t arrive in Taiwan as liberating heroes. Furthermore, the Cold War defiance against Communist China was a prolonged standoff with relatively few hot flare-ups.

The best account of the clash between Koxinga and the Dutch is history professor Tonio Andrade’s masterpiece Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First Great Victory over the West (2011). It’s gripping from start to finish, filled with fascinating details, explanations, and cliffhanger chapter endings. Even in the sections covering the middle of the long siege, where you’d expect a lull in the tension, there are incredible side stories, such as an epic long-distance sailing feat that almost turned the battle, or an amusing, equally “what if” accidental encounter, that could have led to Manchu–Dutch cooperation in defeating Koxinga.

Lost Colony has a profile of “characters” at the start of the book. This dramatis personae is useful and funny, though at times slightly jarring in its flippancy. For the Chinese general “Chen Ze” we get: “Brilliant commander on Koxinga’s side. Defeated Thomas Pedel with clever ruse. Defeated Dutch bay attack with clever ruse. Was defeated by Taiwanese aborigines in clever ruse.” For traitor Hans Radis we get: “German sergeant who defected from Dutch to Koxinga with vital military advice. Liked rice wine.” Entries for three of the Dutch leaders end with a suggestive observation about the last governor, Frederick Coyet: “Coyet hated him. He hated Coyet.” History has treated Coyet kindly, portraying him as a courageous, dogged, and intelligent leader, a hero who was badly let down by incompetent Dutch leaders in Batavia and then unfairly made a scapegoat. This picture was partly of Coyet’s own making; he wrote an influential memoir blaming the loss of the colony on Dutch political and military leaders. Historians through the centuries have accepted and repeated his accusations. Near the end of the book Andrade suggests the fault for the personal animosity and feuds – and the negative consequences that resulted from them – lay with Coyet. Though there’s no doubt what Coyet achieved was remarkable, Andrade says the last governor seems to have been “a difficult man, indignant, quick to avenge perceived slights.”

Lost Colony has the overreaching subtitle: The Untold Story of China’s First Great Victory over the West. While the story of the battle for Fort Zeelandia in 1661–1662 is little known to those unfamiliar with Chinese or Taiwanese history, it’s hardly untold. Nor can it be called a “great victory over the West,” seeing as it involved a small Dutch outpost holding off a numerically superior force of battle-hardened Chinese troops for nine long months. In the acknowledgements, author Tonio Andrade, a professor of history at Emory College, explains that the title was the publishing team’s idea and he agreed to it only after their insistence that it would give the book wider appeal.

At the end of the day, the title and cover of a book are the publisher’s call, so I can’t fault Andrade for backing down. The overreach in the title, however, does extend a little into the book itself. The problem for Andrade is that he is interested in comparing the military technology and techniques of Europe and China; but before the First Opium War of 1839–1842 there were very few conflicts to gauge the relative strengths. This lack of Chinese–European military clashes raises the importance of the Zeelandia episode for comparative purposes. Andrade’s conclusions are that Dutch technology proved superior in several important areas. Although Chinese cannons and muskets were just as good as the Dutch ones, and Koxinga’s soldiers were well trained, disciplined, and experienced, the Renaissance fortress and the broadside sailing ship gave the Dutch an advantage. Koxinga had lain siege to Chinese cities with walls that dwarfed those of Fort Zeelandia, but he was thwarted by the Dutch fort’s ability to deliver deadly crossfire, and “it wasn’t until he got help from a defector from the Dutch side … that he finally managed to overcome it.”

Andrade says that “Coyet, with his twelve hundred troops, might well have won the war.” Koxinga prevailed because of superior leadership and men: “His troops were better trained, better disciplined, and most important, better led than the Dutch. Bolstered by a rich military tradition, a Chinese ‘way of war,’ Koxinga and his generals outfought Dutch commanders at every turn.”

Though this is a reasonable assessment, it’s important to remember we’re not comparing like with like; Koxinga was the experienced military leader of a large force, while Coyet was a colonial administrator for what was essentially a trading company. Though the VOC had pseudo-governmental powers, the bottom line was profits. The Dutch were in Taiwan first and foremost to trade with China and Japan, not to conquer territory, and this fundamental point affected their willingness to spend blood and treasure in defense of the colony.

* * *

In our next installment of Taiwan in 100 Books, we’ll look at a wonderful novel about the clash between Koxinga and the Dutch, and we’ll also cover a travel guide dedicated to the period and its legacy.